A few weeks ago, I had a conversation with a friend where she described a particular incident that she had with her husband. There was a disagreement, and feeling so out of control, my friend locked herself in her car alone and started screaming. “My voice was gone the next day,” she told me. She just needed somewhere for the anger to go, and that felt like the only place for it to escape. Did I understand?

I told her yes, of course I understood, and no, of course I didn’t judge her, because I was her. Just a week before, I was pacing around our bedroom in a state. Ben and I were scheduled to meet friends for dinner, and I was completely burnt out. Work had been piling up, we’d overbooked ourselves for six consecutive weekends in a row, and as much as I wanted to see my friend, I wanted to bail, but felt guilty for canceling at the last minute.

So unable to deal with the oppositional forces of wanting to be a “good friend” and wanting to collapse into bed and sleep for 16 hours, I started pulling at my hair. At one point, I fell to my knees, pressed my face into our mattress, and screamed. The dog was barking, panicked. Ben, unsure of how to handle my emotions, focused on calming her down. (A smart move, as I was past the point of being comforted.) I eventually gathered myself, put on some clothes, and cried the entire way to the restaurant.

That reaction isn’t normal. But the rage that I and the women in my life seem to be reacting to lately has become a normal part of our lives: Violent outbursts over too many boxes in the living room. Screaming matches over being asked, completely innocently by a partner, if we’re free three Saturdays from now to go to a friend’s place for dinner. Hot, panicked tears streaming down your face after realizing that you’ve overcommitted yourself, wanting to be a good friend and a good partner and a good daughter so much so that you’ve forgotten to be good to yourself.

I’ve been trying to pinpoint where these frenzied reactions are stemming from.

Rebecca Traister lays out the history of female rage in her 2018 book Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger. (Written years before Roe v. Wade would be overturned and before embryos in Alabama had more rights than a pregnant woman, but relevant nonetheless.) “Women’s anger has been buried, over and over again,” she writes. “But it has seeded the ground; we are the green shoots of furies covered up long ago.”

I identify as one of those green shoots of buried fury. I am angry about all of what Traister discusses in her book. But lately, I’ve been curious about the smaller injustices. The personal-level slights. The societal ways in which we’re told to keep a lid on our anger, to bury our feelings, to shoulder the burdens and keep moving on — because that is women’s work.

I recently started seeing a new therapist (you know, so I don’t scare the dog with one of my meltdowns again), and in one of our introductory sessions, I said I saw myself as being part of a bridge generation. Both of my grandmothers were married at 19 and 20, having not gone to college, with the understanding that being a wife and mother was the only acceptable route for a woman of that time. My mother, on the other hand, is a college graduate who, after getting married at 25 and welcoming me nine months later, stopped working outside of the home, choosing to focus on motherhood and homemaking instead. That was a choice she made, a choice that was not offered to her mother, and one that she knew would not make me, her only daughter, happy. She tried her best to support a different path for me.

So I went away to college. I was hired at a dream job three months before graduation. I lived alone, and traveled with friends, and dated plenty of boys (and a handful of men). I had a life that my grandmothers could have never imagined for themselves. Before she passed away, my father’s mother squeezed my hand and told me she wasn’t worried about me, because I had a full and beautiful life. And I believed her.

But the past is hard to shake. Even as I was building this alternative life for myself, I still felt burdened by expectations of traditional femininity. They clung to me like burrs, and no matter how I tried to pick them off one-by-one, they stayed there, stuck, waiting to snag my hair and scrape my hands. How important it felt to find a man to marry. How vital it felt to have children. How often it would be remarked by members of my family that I would give up my career when I finally hit those true markers or womanhood. (In this economy?!?!)

A family member once remarked to me, after I lamented my inability to find a partner to settle down with, that they wished they could be a fly on the wall during one of my dates. “You must be doing something to put men off,” they said. “I hope you aren’t like you are with the family like you are on dates.” I withered, thinking about how earlier that day, I’d gotten into a particularly heated argument with one of my Republican family members, and how closely it had followed a (markedly less-vicious) tête-à-tête I’d had with a date the weekend prior. Even now, older family members like to tell Ben how good he is for me. How much he’s calmed me down. How much more pleasant I am to be around now.

The message has been clear to me for a while: I have not behaved like a “good” woman, which is why I was alone. The past decade of my life have been an effort, then, to fit into that mold of “goodness,” and if I had to guess, that’s why my friends who are around my age are screaming, too.

We’re the people-pleasing generation. There’s a reason why so many TikToks about Millennial managers have us cowering to our bosses, staying on until 9 PM to finish wholly unimportant work, while telling our direct reports to sign off early to protect their mental health. We were raised by a generation of men and women who were still so deeply rooted in the past that, although they encouraged us to seek a different path, they instilled in us that traditional idea of femininity. It’s my belief that this is why there’s still inequality in domestic work — why, although 61% of families with children have both parents working, society looks to the woman to know when school closures are happening, or to do the laundry on her lunch break, or to spend her precious mornings before the kids are up researching slow-cooker recipes and ordering organizational bins on Amazon.

And even women like myself, who have not started procreating quite yet, are still caught in this loop. We need to be the perfect girlfriends, and friends, and employees. We need to say yes to everything, to always be up for sex, and to spread ourselves so thin for others that there is nothing left for ourselves. We’re the girl bosses, the wonder women, the chicks who can really have it all. (Insert America Ferrera’s speech in Barbie here.)

But nobody told us how exhausting keeping all those balls in the air is. Nobody talks about how burnt out they are. It’s why “no” continues to be the hardest thing to say. It’s why we lock ourselves in our cars and scream. It’s why we snap at our partners about boxes, and groceries, and vacuuming the rug. It’s bubbling up, frothing out, spilling over. It’s rage.

“Maybe we cry when we’re furious in part because we feel a kind of grief at all the things we want to say or yell that we know we can’t,” Traister writes. “Maybe we’re just sad about the very things we’re angry about.”

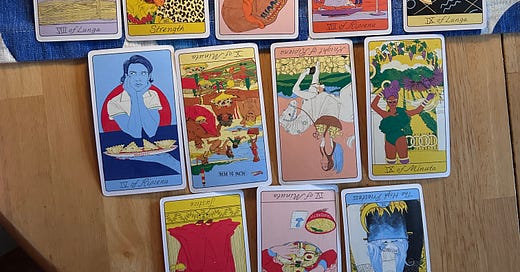

I gave myself a tarot reading on my birthday last Friday. For my year-in-summary card, I pulled the eight of swords, which shows a woman bound and blindfolded, surrounded by (you guessed it) eight swords. She believes that she cannot escape the prison that has been built for her. But, the tarot guides, if she were to just remove her blindfold, she would be able to escape her predicament with ease.

Earlier that week, my therapist had asked me what would happen if I just chose to ignore what I thought I needed to do in order to be “good” and instead listened to what I actually wanted. I thought about this as I looked at the card that I’d just pulled. If I chose to remove my blindfold, to ignore the “shoulds” of life, and society, and femininity, and figured out a way to tap into a picture of life on my terms — whether that was on a macro-level, like what kind of wife and mother I actually want to be, or on a micro-level like whether or not I actually wanted to keep my dinner plans on a Saturday night — what would that look like? Was I even capable of doing that? How would I even go about trying to break this cycle?

I continued pulling cards. The 10 of wands in reverse — pointing to my holding on to burdens unnecessarily and my trying to figure out ways to lighten my load. The nine of pentacles, which speaks to feelings of peace, and the declaration that I deserve comfort. And when I finally got to my last card, number 12, the card that would illuminate the path to where I was headed, I pulled the High Priestess in reverse. She calls on you to listen closely to what your inner voice tells you. What parts of your unconscious are you denying? What is it trying to say?

Looking down at my spread, I considered whether that inner voice that I had been denying was what was ripping out of me in my lowest moments. Maybe it was the voice of some internal High Priestess ringing inside of a locked car, or being projected out during an argument, or being smothered into a pillow in desperation. Maybe that is truly where I am headed — in a direction that prioritizes myself, where I don’t care how the world perceives me, where I am able to listen to that voice inside of me that says, “You don’t want this,” and actually follow through.

Scrolling through my Instagram this Friday, International Women’s Day, I came across the words of the poet and activist Swati Sharma: “I am a woman, and I get to define what that means.”

Maybe it’s as simple as that. Maybe that is the anecdote to this righteous, internal, wholly-female rage.

As an eldest daughter (also Italian American) prone to people pleasing this resonates so deeply!!!

So true. We can't do it all. Just not possible and, so what? Really what's going to happen if you cook a bad dinner, miss a social event, don't sweep the floor, do less than your best on that article, forget the boss's birthday, call in sick and just take the day off? We punish ourselves and no one else really cares that much.